Ditch the Lawn, Go Native

That swath of green outside the front door comes with a high environmental price. Lawn maintenance accounts for one-third of residential water use, the equivalent of seven billion gallons of water per day, and consumes 800 million gallons of gasoline annually and up to seven pounds of fertilizers and pesticides per acre.

The latest landscaping trend involves swapping sod for native species. Natives, plants indigenous to a region and adapted to the growing conditions, improve soil fertility, reduce soil erosion, require less fertilizer and pesticides—reducing runoff—and provide food and shelter for wildlife.

“We’re starting to look at the broader environmental impact of our lawns and realizing that replacing them with native grasses has significant environmental benefits,” says Cassy Aoyagi, a sustainable landscape designer and owner of FormLA Landscaping in Southern California.

A New Perspective

Researchers at a demonstration garden in Santa Monica, California, found that over the course of a year a sustainable landscape used 51,000 fewer gallons of water, created 420 pounds less waste and required 65 less hours to maintain than a traditional lawn. And ecologists at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center at the University of Texas also discovered that native landscapes suppress weeds better than traditional lawns.

Gordon Ownby believes a native landscape is more aesthetically appealing, too. In 2008, Ownby hired FormLA to replace the lawn of his La Crescenta, California, home with native plants like dymondia, a ground cover; evergreen shrubs called manzanita; magnolias and California lilacs. Although he made the decision for practical reasons, including water savings and less maintenance, Ownby discovered that his natural landscape had additional benefits.

“I was surprised at how pleasing native plants are to the eye; I find the palette much more relaxing than a bright green lawn,” he says. “It also gives our house some distinction on the block.

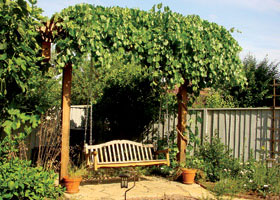

Before transitioning the lawn from turfgrass to native plants, Ownby rarely spent time in his yard. Now, he looks forward to spending evenings in the garden with a glass of wine. “It feels more natural,” he says.

Redesigning Your Lawn

Achieving a natural landscape will take some knowledge and effort, according to Evelyn Hadden, author of Beautiful No-Mow Yards: 50 Amazing Lawn Alternatives (Timber Press) and founding member of the Lawn Reform Coalition. “There is a learning curve with native plants,” she says.

Hadden recommends working with a landscape designer who specializes in sustainable landscapes, taking classes through a local native plant society (check plantnative.org) or consulting with nursery professionals for site analysis, design and plant selection.

Plants should be chosen based on elements like sunlight, soil quality and drainage. Of course, aesthetics are important, too. “One of the biggest reasons that people don’t take the step is because they find it difficult to imagine anything but an expanse of green lawn,” says Aoyagi.

But with native plants, possible design styles range from woodland gardens to desert landscapes to rain gardens. “We don’t want people to feel boxed in when they go native; we want them to feel like they have options,” she says.

Native Steps

Despite their growing popularity, native plants are still difficult to find, especially at retail nurseries and big box stores. Native plant societies are the best source for purchasing the plants. There is a cost, too. Aoyagi estimates that transitioning from turfgrass to native plants will cost a minimum of $4 per square foot.

To ease the expense of going native, Hadden suggests renovating the landscape in stages, creating a plan for the entire site but implementing it in stages. It’s also essential to focus on the payoff as opposed to the upfront costs

Replacing turfgrass with native plants will provide immediate savings because it requires less water and fewer chemical pesticides and fertilizers. Native landscapes also require less maintenance, translating into ongoing savings.

And beyond the environmental goals of reducing water use, chemicals and gas-powered mowers is the benefit of reconnecting with nature.

“The goal is to work with nature instead of against it,” Hadden says. “It is a process but it’s one that reconnects you with your outdoor space in meaningful ways.”

JODI HELMER is the author of The Green Year: 365 Small Things You Can Do to Make a Big Difference(Alpha). Visit her at jodihelmer.com.