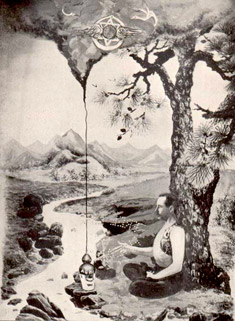

COMMENTARY: Yoga Two Ways

Natural Connections & Buried Fears

From

Among these branches, the yama teachings of ahimsa (non-violence), asteya (non-stealing) and aparigraha (non-greed) are most relevant to the concerns of environmentalists. Ahimsa, as it is thought of both by many yoga students and environmental activists, includes abstaining from meat.

"Just because the killing is done by somebody else, somewhere else, does not mean the karma, the responsibility, is not yours," says Sri Swami Satchidananda. For yoga followers and environmentalists alike, the assault on both animals and the environment (especially in terms of deforestation and inefficient use of grain crops fed to cattle) is one of the primary ways in which we can minimize our collective environmental footprint.

Protesting our modern agricultural system through a vegetarian lifestyle also involves the principles of asteya (non-stealing) and aparigraha (non-greed). With starvation around the globe, the grain given to livestock could in theory be used to feed millions of hungry people, so followers of these principles could conclude that both greed and stealing are inherent in eating meat. With 16 pounds of grain needed to produce one pound of meat, vegetarian yogis and environmentalists are devoting their practice to changing the inefficient methods of food distribution throughout the world.

Although abstaining from meat is a significant commitment for both yoga and the environment, connections between yoga philosophy and the environmental movement are not exclusive to vegetarianism. In our daily lives we encounter violence, theft and greed everyday, but what both yoga and environmentalism teach us is that the first step to igniting social change is greater consciousness of our actions on an individual level, which will lead to a collective difference on our planet.

Fear of Yoga: A Long Path from "Free Love" to Respectability

By Jim Motavalli

Although it has a benign image now, with two Time magazine covers and 16.5 million American adherents, yoga was once much feared in the U.S. as a "love cult." Robert Love wrote a fascinating piece on this subject, originally for the Columbia Journalism Review but reprinted in the March/April 2007 issue of Utne.

Love writes: "Yoga arrived in the United States in a cloud of ideas both sacred and profane from what was called the Orient: the vast, exotic, unknowable out there. In 1805 William Emerson, father of Ralph Waldo Emerson, published the first Sanskrit scripture translation in the United States. His son Ralph and his Transcendentalist posse, especially Henry David Thoreau, were dazzled by the Bhagavad-Gita, which Emerson read in translation for the first time in 1843, and other Indian spiritual texts."

All fairly respectable, but as American xenophobia grew, the tide turned against yoga. Again, from Love"s story: "In June 1910, the month Congress unanimously passed the Mann Act, known as the White Slavery Act, the American yogi Pierre Bernard was jailed for abducting two young women in New York City; a week of sensational press coverage, in which he was forever branded the Omnipotent Oom, the Loving Guru of the Tantriks, ensued." Here"s a typical headline from William Randolph Hearst’s New York American: "Police Break in on Weird Hindu Rites: Girls and Men Mystics Cease Strange Dance as "Priest" Is Arrested.""

Sensing a great story, the sensationalist press swooped down. In 1911, the Los Angeles Times published "A Hindu Apple for Modern Eve: The Cult of the Yogis Lures Women to Destruction." The colorfully written story proclaimed, "These dusky-hued Orientals sat on drawing-room sofas, the center of admiring attention, while fair hands passed them cakes and served them tea in Sevres china." Later that year, Current Literature warned that yoga was leading America to "domestic infelicity, and insanity and death."

The tide began to turn with the arrival on these shores of Yogananda, whose Autobiography of a Yogi was published in 1946. Yogananda didn"t have an easy time of it initially—he was hauled into court in Los Angeles and run out of Miami by 200 angry husbands. But yoga was beginning to catch on as a non-controversial method of relaxation, and it was endorsed by such diverse figures as Congresswoman Frances P. Bolton (R-OH), the actor Gary Cooper and, in 1967, the Beatles, who went to India to study with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

Today, no one bad-mouths yoga, and Yoga Journal has 350,000 subscribers. California celebrity physician Dean Ornish declared that yoga-based stress management can help with heart disease, and the results of his study were published in the distinguished medical journal Lancet.

Love concludes, "There are some 78 million baby boomers living and breathing and getting older. In fact, 7,920 more of them turn 60 every day. If I were a betting man, I would lay odds that yoga is not about to disappear again for a long time to come."

Sources: The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali by Sri Swami Satchidananda and Integral Yoga Teachers Association Newsletter, May 2007.

Robert Love"s article in Utne is here.

KATHRYN GUTLEBER is a student at Connecticut College and a former E intern. JIM MOTAVALLI is the editor of E.