Flushed With Success

New Waste-Reducing Designs in Modern Toiletry

Every day, Americans flush away about three billion gallons of drinkable water, not to mention millions of pounds of useful fertilizer. As Sim Van Der Ryn notes in his classic 1978 book The Toilet Papers, “Our excreta-not wastes, but misplaced resources-end up destroying food chains, food supply and water quality in rivers and oceans….How did it come to pass that we devised such an enormously wasteful and expensive system to solve a simple problem?”

How indeed. In the ancient Orient, a sensible system developed whereby waste was collected on traveling carts, then brought to dung heaps for decomposition. In the West, chamber pots were simply dumped in the streets, creating serious health hazards, until the renowned Thomas Crapper invented the flush water closet in Victorian England. His sit-down unit was derived from the traveling commodes used by English and French kings dating back to the 16th century (hence the term “throne”?).

Waste Not

The toilet is probably the last thing you think about when eco-fitting your home, but there have been some remarkable technological advances. For one thing, the modern flush toilet isn't as water-wasteful as it used to be; federal guidelines now prohibit the use of more than 1.6 gallons per flush in new units, producing a 25 percent water-use reduction for the average family. Unfortunately, the low-flow toilets are producing performance complaints. “They don't work,” says a Reston, Virginia homeowner. “You have to scour the toilet every time you use it.” Flushing twice-as some consumers do-cancels out the water savings. Pressure-assisted models cost more than gravity-flush units, but eliminate the headaches.

Most people don't acquire a new toilet too often, but in California, towns like Pico Rivera are giving away $100 low-flush units, to save local water supplies. In Hawaii, Honolulu residents can get a $50 to $100 tax credit for installing a low-flush toilet.

Even more environmentally friendly is the dry composting toilet, a variant on the privvy seen in 19th century Japanese inns (which valued their guests' wastes so highly as fertilizer that rates went down with each additional person staying in the room). Composters don't provide a solution for apartment-dwellers (the required infrastructure is too complicated), but they're an ideal solution for many homeowners.

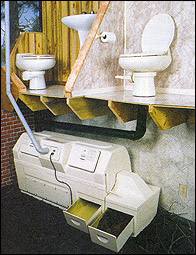

The elegant Clivus Multrum composting toilet originated in Sweden. The company, owned by American heiress Abby Rockefeller, is now based in Massachusetts. The basic design is very simple. Waste drops down a chute from the toilet into a coffin-like, vented chamber canted at 20 degrees. A variation on this approach to the biological toilet uses a smaller chamber that incorporates a fan to aid in ventilation (and, sometimes, a heating element for faster decomposition).

Rodney DiClemente of Clivus New England says the Model 12 ($7,000) is best for home use, with most buyers using it in conjunction with a Japan-built foam flush toilet. DiClemente reports a dramatic upsurge in home installations since Massachusetts passed Title V, which includes much more stringent requirements for septic installations. “Some people just don't have the land necessary for the big leaching areas that are required,” she says.

Of course, $7,000 may seem like a lot for a toilet when you can buy a standard one at the hardware store for $200, but it's more apt to compare the Clivus and Sun Mar to an entire septic system. Title V retrofits can cost $20,000, and Clivus reports that 95 percent of its customers buy the units for economic, not environmental, reasons.

Composting toilets for the home are becoming especially popular in rural areas beyond the reach of sewer lines. One very satisfied customer is Al Dahl of Kellogg, Idaho, whose home on a steep hillside made installation of an effective septic tank difficult. Dahl's solution was a Sun Mar Centrex Plus, a $2,000 unit installed in the basement (connected to the $200 air-flush toilet in the bathroom by straight pipe) and vented outside. “I'm overjoyed with this thing,” says Dahl, who says the single toilet happily supports five people. There's absolutely no smell.” Every two days, Dahl goes down to the basement and turns the Sun-Mar's fan- and heater-equipped biochamber with a hand crank. He estimates that by this spring he'll be using finished compost on his garden. “People aren't sure they'll want to eat the vegetables, though,” he kids.

Hiking Hazards

The incredible popularity of hiking and climbing has made waste disposal a big topic for outdoor recreationists, even inspiring books like Up Shit Creek: A Collection of Horrifyingly True Wilderness Toilet Misadventures (Ten Speed Press) and organizations like Hikers Against Doo-Doo International. Paul Cunha of The Appalachian Mountain Club's Pinkham Notch camping facility in New Hampshire says he's “very pleased” with the Clivus Multrum units installed at the visitors' center and the huts. A simpler solution is being pursued by the Green Mountain Club in Vermont: worm hole privvies. These easily-constructed outhouses are stocked with red worms, already a staple of home composting setups. The worms eat the waste, eliminating the increasingly thorny disposal problem. The trick, apparently, is balancing the worm population with the waste load. Too much waste and the worms get smothered; too little and they starve.

JIM MOTAVALLI is editor of E.