Flying Clean

Airline Recycling is a Hit-and-Miss Proposition

Call it a fly-by-night operation. A flight attendant zips down the aisle, grabs an empty soda can from an airline passenger, mumbles any old answer when asked if it will be recycled, and stuffs the can in a trash bag. There’s really no way of knowing if the soda cans, newspapers, juice or liquor bottles that pile up on long flights are sorted and recycled. U.S. airlines are not required to meet any federal recycling regulations.

Fort Lauderdale’s international airport recycles its waste, but much of the paper, plastic and aluminum from commercial flights is trashed.

Airport Recycling Specialists

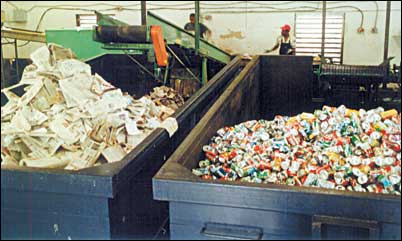

When asked if there’s a need for a federal recycling plan, Andy Duerr, vice president of Airport Recycling Specialists (ARS), says, "I certainly think so. Don’t you?" Duerr and his company showed how airline recycling can work when it was hired in 1989 to handle incoming planes at Florida’s Fort Lauderdale international airport. Nine workers manually sort the trash during the day, plucking out aluminum, mixed paper, steel cans, corrugated cardboard, three types of plastics and all colors of glass. It is cheaper for the airport to hire ARS than to pay a trash hauler, says Duerr, since garbage disposal costs have risen 180 percent in the last decade in Broward County. The company also recycles trash accumulated in airport terminals and offices.

At other airports, some airlines have taken the reduce-reuse-recycle mantra to heart and are doing it themselves. Officials at Midwest Express Airlines, with hubs in Omaha, Nebraska and Milwaukee, claim they are the first to bring dedicated recycling bins on-board. At the end of a trip, flight attendants walk down the aisle and ask passengers if they need newspapers or aluminum cans recycled, says Lisa Bailey, a spokesperson for the airline.

Southwest Airlines maintains two trash bins at the back of each of its planes: one for aluminum and one for waste. Paper products are not recycled because "it would be so hard—you have so many varieties," says spokesperson Angela Vango. Plastic, throwaway silverware is not used since the airline serves only "finger food" and not full meals. When flight attendants walk down the aisle to collect trash, they sometimes follow with a "recycling" bag, says Vango.

Alaska Airlines also does some recycling of aluminum, says spokesperson Jack Walsh. American Airlines recycles aluminum cans through a Los Angeles-based program it developed. On Continental Airlines flights, recycling is left to the catering company. Flight attendants separate trash from the recyclables on-board, but contracted caterers at each airport decide whether it will be recycled, says spokesperson Ben Clark.

America West Airlines, citing low quantities of recyclable products, only recycles at its two hub cities, Phoenix and Columbus. "We don’t have enough volume in those "spoke" cities to get it organized and get the project going," says Janice Monahan of America West, who adds that additional recycling would depend on cooperation from third-party catering companies. Revenue the airline raises from recycling collections is donated to United Way and Pegasus, an organization that assists financially needy or ill flight attendants.

Some airlines cite storage problems as an obstacle to strict recycling programs. If an aircraft can’t drop off its recyclables until it has gone through a handful of connections, they say, it’s easier to just throw it in with normal trash at the next airport. "We found it was logistically difficult, if not impossible, to arrange for those soda cans to be picked up," says David Castelveter, a spokesperson for US Airways, which axed its in-cabin program five years ago.

US Airways had required flight attendants to collect recyclables in a special bag and store them separately from other trash. But if only some of the 203 airports the airline services pledged to recycle, the flight attendants might be easily confused, says Castelveter, who adds that it would be tough to teach proper handling of recyclables when flight attendant responsibilities shift often.

According to Duerr, "Soda cans make up one percent of the garbage. They take up little volume and are lightweight." Some airline officials see it differently. National Airlines" solution was to do away with cans altogether. Fed up with the frustration of housing a day’s worth of soda cans in the cabin, the airline recently partnered with Sterling Beverage Systems to develop a soda fountain concept on its drink carts. Called a "post mix technology," syrup and carbonation are stored separately on the drink cart, but combined when a customer asks for soda.

"It reduces space," says Dick Shimizu, director of corporate communications. "Sometimes on a flight you open up four to six cans of soda and none of them get finished." The soda fountain is currently on only two of the airlines" 18 planes, but will likely be on all of them by year’s end.

Some airlines have introduced "green" paper products in their cabins. America West’s Monahan says cocktail napkins used throughout the cabin are made from recycled paper, as are menus given to first-class passengers. Also, trash bags used in the cabins are made from recycled materials.

Duerr says he is getting calls from other airports interesting in piggybacking on his recycling program, or perhaps starting up their own. He frequently references a study done in the 1990s that argued for banning newspapers from flights, saying there would be more space for fuel. "It’s astronomical how much newspapers and magazines weigh," says Duerr.

U.S. carriers could perhaps learn from China Southern Airlines. In May, it announced a three-part program called "Green Cabin." Only environmentally sensitive cups and catering utensils are used, and video programming and commercials about environmental protection are featured as in-flight entertainment service in both Chinese and English.