Just Doing It!

Tired of Slacker Stereotypes, and Lip Service, Generation X Proves That Actions Speak Louder Than Words

Just Doing It!

Awakening to the sounds of The Chemical Brothers, Jennifer Rivera flips back the covers and begins her day. After indulging in a four-minute shower, feeding the orphaned cat her ex-neighbors left behind, fixing her lunch and donning hastily-grabbed clothes, she dashes out the door to catch the subway to her job as a first grade teacher for the City of New York. After work (and a field trip to a community recycling center where she shows her students the importance of the three Rs), Jennifer volunteers at the community garden on 9th Street. She also does river clean-up on the Hudson on weekends, finds time to spare for The Literacy Project on Thursday nights, and grocery shops for her 94-year-old landlady each Sunday morning. When asked how she finds time to get it all done, Rivera replies: “It makes me happy doing things for others, for my community. There are so many things that are wrong with this country, and this is my little part at setting things right.”

The key to getting things done, her generation believes, is grassroots action, not lip service. Rivera represents one of a growing number of young adults that have moved beyond the hallmark issues of Baby Boomers-“recycling, saving whales and hugging trees”—and onto a greater diversity of issues. She says neglected neighborhoods, declining educational standards, environmental degradation and immoral politicians, along with the Internet and “a great entrepreneurial spirit,” are responsible for influencing her generation—the so-called Generation X.

Generalization X

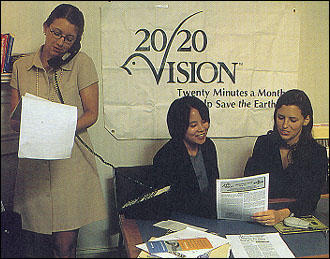

The young activists at 20/2 Vision get people involved in social change through letter-writing campaigns.

“Generation X” was first a punk band in the early 1980s. But it wasn’t until Douglas Coupland’s similarly titled novel that the term made it into Time, Newsweek and Fortune as a description of the seemingly apathetic children of Baby Boomers (born between 1945 and 1965). In the years since, the term has become the much-loathed namesake of some 50 million Americans born in the late 60s and 70s. X’ers themselves insist they are anything but the “slackers,” “hackers,” or uncaring, body-pierced youth portrayed in mainstream media. They are boldly proving that today’s young adults have purpose, determination and a plan for changing the face of America, one neighborhood at a time.

Where, then, is the environmental movement heading as Generation X increasingly replaces its parents in key leadership roles?

Adam Werbach (see Conversations, this issue), who last year became the youngest president of one of the oldest environmental organizations in America, feels the change is for the better. The Sierra Club, whose members are mainly in their 40s, needs to reach out to energized youth and use their skills for building better communities, Werbach says.

Young adults are starting to take action in a big way. Community gardens, many started by youth groups, are turning abandoned industrial sites into beautiful public spaces. College students can be seen emailing, faxing and lobbying for better education, cleaner air and water, and the end of corporate polluting. Twentysomethings are influencing consumers by starting eco-companies and selling environmentally-responsible products. “I think we understand our historical responsibility, in terms of being the generation that makes or breaks it,” says Danny Kennedy, 26, who became an eco-activist at age 14 in his native Australia.

Additionally, service leaders agree they’re experiencing significant increases in young adult volunteers. According to a 1992 survey by Independent Sector, an organization that monitors volunteerism and philanthropy, almost half of 18- to 24-year- olds volunteer, a figure which has been climbing steadily since 1988. X’ers themselves feel the increase is due in part to economic hardships during their teen years, along with a decreasing sense of community. “What I find a lot of the time is that if youth aren’t involved, it’s because they don’t know how to get involved,” says Angela Brown, a recipient of the International Human Rights Award who began fighting a proposed PCB landfill at age 13. “Adults don’t know how to bridge that gap. Nobody’s talking to each other. But everybody’s talking about each other.”

Young adults are also witnessing global conditions worsen: the rapid loss of species and their habitat; startling effects of accumulating toxins in our bodies and the environment; increasing depletion of the ozone layer; and elected officials pilfering young pockets. Yet the world is also pulling up to the drive-thru of the Information Age-a one-stop digital extravaganza that offers historic leaps in areas like art, science, health and environmental studies—a drive-thru with X’ers behind the wheel.

Many “Gen X” analysts point to trends in fertility and birth rates as defining the beginning and ending points for X’ers. Others say it’s the shared experiences which define them: divorced parents, the Reagan years, MTV, ozone holes, the Gulf War, the threat of no Social Security and an increasingly dysfunctional educational and healthcare system. “We are not a Generation X, but a generation which has inherited a degenerated world,” says Werbach, 24, re-elected last May as president of the Sierra Club.

According to the Census Bureau, “Generation X exists only in the minds of marketers,” marketers who are desperately trying to pigeonhole these “baby busters” in order to sell them something.

McJobs

Between 1979 and 1995, 43 million jobs were lost to corporate downsizing. Not only are jobs being cut back, but increasingly, there is no sense of a work community-a place where workers are appreciated for their merits and individuality. Twentysomethings have watched their parents’ occupational agonies in awe and wondered: why isn’t anyone changing the face of business and how we get things done?

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals organizes young activists to protest fur, factory farming and animal cruelty.

X’ers now work 3.6 percent longer each week than the national average, becoming better educated and grassroots oriented than their older counterparts. And while Generation X’ers worry about their current economic future, they’re also decidedly optimistic as individuals that if they work hard enough, they’ll achieve their goals—creating socially responsible businesses, safe communities and a healthy environment.

Interest in corporate careers is sliding. Entrepreneurialism and grassroots volunteering have taken their place. Mitch Cahn, the 29-year old president of Headcase, a New Jersey-based manufacturer of hemp clothing and headwear, says, “We’ve got a very libertarian generation. The difference between us and the liberal generation that proceeded us is that

we see capitalism as something that’s not necessarily evil. We see we can use capitalism for social change. It’s one way to make government and big business stand up and take notice.”

A 1993 University of Michigan study found that 25- to 34-year-olds are starting businesses at three times the rate of 35- to 55-year-olds. X’ers are getting away from corporate control and the cubicle mentality, and doing what they want, when they want-while making headway for green businesses.

Cahn says that when X’ers graduated from college “the economy was pretty bad-after 10 years of it being great. A lot of us were not able to get jobs. But the information age was booming, environmental companies were popping up—a lot started by our age or younger. Most of us just wanted to make a good product without using materials that destroyed the Earth.”

A recent study by Infocus, Inc. found that 42 percent of adults aged 18 to 34 tried a new product because they felt the product, its packaging, or the manufacturer benefited the environment; 51 percent switched brands because of environmental concerns.

Generation X is “turned off by anything that seems cliché or insincere,” says Judith Langer, president of Langer Associates, a New York City market research firm. She says retailers shouldn’t make claims of social or environmental responsibility unless they can back them up, because X’ers read labels seriously.

Ocean Robbins, co-founder of YES! Camps, which educates young adults on key environmental and social activism issues, says young adults are heading away from a consumer culture, and toward a multicultural view of the Earth and its resources: “The diversity most of us know is the incredible variety of human-made things, like lamps, cars, houses, disposable packages and other manufactured items.”

Many X’ers are standing up and tuning out ad rhetoric, realizing their consumer choices make a big impact on the environment. Eco-retailers say business is booming, and it could be because X’ers are putting their money where their mouth is and buying non-animal-tested, recycled and recyclable products created by companies that invest in communities.

According to a 1996 Who Cares magazine/Center for Policy Alternatives study, “young people have high expectations of business and 79 percent” believe businesses have an obligation to give back to their community. Consequently, 90 percent “support raising fines on businesses that pollute the environment or discriminate.”

Settling Down

Mitch Cahn founded the eco-company Headcase at age 24.

Yet, while safe neighborhoods, clean air, and a better environment are major concerns for most X’ers, several studies point to the fact that this generation holds aloft the American Dream: An overwhelming 92 percent of X’ers said “the American Dream is something I really want to achieve,” according to a recent Yankelovich Partners study. Purchasing a car, settling down, and buying a house are very important to some X’ers, a conclusion reflected by several polls.

Meanwhile, 82 percent of twentysomethings polled feel they have to compete and be aggressive to obtain the Dream and two-thirds said “material things, like what I drive and the house I live in” were important. But underlying this seemingly materialistic mindset is a strong anti-materialistic sub-culture, which views happiness over materialism.

One Who Cares survey cites 66 percent of young adults agreeing that “a simpler life is a better life.” When asked if X’ers are overmaterialistic, Cahn replies: “I definitely don’t think so. They’re interested in quality, not quantity. And the entrepreneurial heroes of our generation are the guys with the long hair and bare feet-the Internet guys. That seems to be a backlash against materialism.”

Cyberpunks

While café lattes and cyberspace go hand in hand for many in this generation, it’s what they do after the caffeine kicks in that counts. As online cafes become increasingly popular with X’ers, so does Internet-based environmental action at such places.

Six years ago, 18-year-old Josh Knauer envisioned the Internet creating a global community of activists-students, volunteers, anyone willing to work for a better world. He set out by linking environmental websites to one another, eventually creating Envirolink, a grassroots online community which grew from a small website with environmental links to one which now links the sites of 130 countries and supports activists with services like daily action alerts, searchable databases and congressional updates. “Older generations have devalued our generation’s individuality. The Internet has helped discouraged this thinking,” says Knauer, now 24. “Our generation is very interested in effecting change and not making the mistakes of previous generations.”

Technology is adding a powerful new component to activism and a fresh spin on what can be effective in the environmental movement. Though there is a lag in getting good quality hardware and training to organizations that need it, tools like the Internet are being used innovatively to network, organize and inform activist communities that are becoming increasingly techno-savvy.

“Technology is phenomenal as far as mobilizing and organizing goes,” says now 32-year-old Brown, who lives in Atlanta and runs the globally-focused Youth Task Force. “It’s now more possible than ever to communicate with activists around the world. Which means that transnational corporations no longer have a monopoly on communication internationally.”

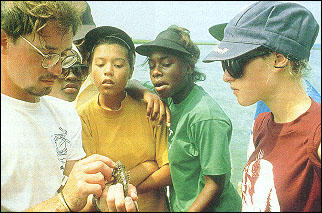

A Student Conservation Association Gen X’er leads a nature workshop.

In Washington, D.C., a national student network called Free the Planet! is using a system that quickly gathers hundreds of personalized letters on urgent issues, turning the emailed messages into faxes addressed to the appropriate targets.“That’s using technology wisely,” says Rick Taketa, 24, who helped create EnviroAction with the Environmental Defense Fund in late 1996. “We can literally shut down the fax capabilities of polluters and politicians [by keeping their faxes eternally busy], while delivering a pro-environmental message. That’s powerful.” A youth-inspired documentary called Connect-which aired on MTV last Earth Day-provided the impetus for the website, which now links activists from across the world to local, grassroots efforts for social and environmental justice in their respective areas. It’s a totally fresh twist on an old, proven approach to activism: People Power.

A recent Wired magazine article articulated what is going through many X’ers minds: “The basic science is now in place for five great waves of technology—personal computers, telecommunications, biotechnology, nanotechnology, and alternative energy—that could rapidly improve the economy without destroying the environment. Moving informatio

n across the United States by fax, for example, proves to be seven times more energy efficient than sending it through Federal Express.” And Gen X knows it.

“Sending an email message can be as effective as a phone call or chaining yourself to a tree, but it all works together. People need to stay involved in their local communities as well as the virtual community,” claims Knauer.

Actions Speak Louder

X’ers now view the environmental future with grave concern: A Rutgers University/ERA study found that only one-fifth of 18- to 34-year-olds believe the environment is improving. This same study also noted that educated people are more likely to volunteer for environmental causes (66 percent of X’ers go on to college-the highest number in history). Some 12 percent of X’ers volunteer specifically for environmental, conservation or wildlife groups. Meanwhile, almost two-thirds of young adults reported that they are doing more for the environment today than three years ago, showing a steady increase in awareness and activism.

Erika Chan, of the political letter-writing activist group 20/20 Vision, says, “X’ers definitely are more educated on the hard core issues like recycling, endangered species, clean air and clean water. The focus back in the 1970s was on making the environment a national issue. Now, we have the time to take action and focus on solutions because the groundwork has been laid for us. The sound bite mentality may work to some degree on X’ers, but you have to have substance beyond the message. I think there’s more environmental interest in this generation than the previous one.”

International Involvement

As once-isolated young activists across the world have begun converging, strong networks have developed and new terms like “majority world”-a witty spin on “developing countries”-have become part of a new global wordset that is fresh and vibrant. As one of the co-founders of Action for Solidarity in Environmental and Economic Development (ASEED), Danny Kennedy has long been at the forefront of a growing youth movement that sees global networking as central to effective activism in the 90s.

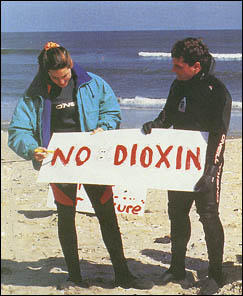

Angela Brown, who firs protested a landfill at age 13, now takes on such issues as Time Magazine’s use of chlorine.

“We began meeting in preparation for the United Nations’ Earth Summit in Rio in 1992. Because [the Summit] was selling us down river, young people around the world decided to target it,” Kennedy recounts. “We proudly were, I believe, the first ever to drop a banner off the United Nations building. That was great: a 10-story banner reading ‘Earth Summit-Hijacked.’”

During that same week in 1992, Bineshi Albert was convening the first Native Youth circle of the Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN) on the banks of the Columbia River in Washington, D.C. While the Earth Summit’s sessions excluded many of the 6,000 youth in attendance, young Native American activists from all over the U.S. solemnly observed the 500-year anniversary of the arrival of Columbus to the Americas. There would not be a repeat of the last 500 years, they vowed.

“It’s never easy working as a youth in the native Indian community to keep traditional beliefs alive,” says Albert. “But there’s a very strong sense that we’re right, and we’ll continue fighting for that.”

As visionary Native American activists like Albert live according to their traditional beliefs, indigenous youth from the South Pacific to the North Pole face non-stop pressures from Westernization and the pillaging of resources on their lands.

For many X’ers, social issues like homelessness, lack of health care, racism, AIDS and environmental problems all go hand in hand. And there’s a consensus that multiculturalism and ending environmental racism (discrimination in toxic dump siting) are the key issues for turning things around.

“I first got involved in the environmental movement when I was 12,” says Brem Wanbantei Blah Lyngdoh, a representative of the Khasi Tribe in Cherrapunjee, India. “I couldn’t stand seeing my homeland destroyed by people who were only concerned about their profits and their self-interest. Coal and uranium mining are turning Cherrapunjee to an eroded desert.”

Lyngdoh, now 23, is a shining example of a grassroots activist who has taken up the global effort to change the playing field. “During my high school days, I was involved in some demonstrations against deforestation—which threatens the existence of our peoples. The government reacted by sending the police and the Army to keep us quiet. It resulted in a riot where many innocent students were brutalized, arrested and even shot at. One of my friends was killed in those riots.”

In western Africa, similar conflicts stem from public support of sustainability. “The current ruling government thinks our student movement is in opposition to them,” says environmental leader Lawrence Amoaful, 23, of Ghana, Africa. “They sent convoys of police to disburse the demonstrators-someone got shot recently. You have to be tough and know that what you’re doing is right.”

Twentysomethings manage to have fun while protesting Mitsubishi’s forestry policies.

As a leader of the Renewable Natural Resources Students Association, Amoaful has co-developed a program called Adopt-a-Village, in which he and his peers journey to remote, mountainous settlements along the west coast of Ghana. There, they work with the local people to educate them in reforestation, family planning and health issues like AIDS. They instruct villagers not to “slash and burn” forests and promote the use of condoms. Amoaful is now planning a trip to the United States to share his model.

Smashing Pumpkins…and Multinationals

“For me, in any struggle,” says Brown, “it’s always the culture. The victories along the way keep the spark going and make it fun. The protests on the lawn, the sit-ins… participating in that kind of thing is so powerful. I love it.” Werbach agrees: “We’re engaged, we’re ready, we’re all mobilizing for a common goal…and we’re having a lot of fun together.”

Meanwhile, colleges across the country are making their mark through innovative programs, networking (via the Net, of course), and mobilizing volunteers to create new organizations and get the work done. Students from Moscow to Maine are organizing around a myriad of issues-clearcutting, dambuilding, endangered species, pollution, clean energy, vegetarianism, alternative transportation, urban gardening and community involvement.

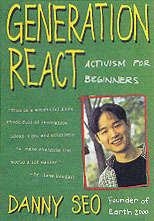

Nineteen year old Danny Seo believes his generation has what it takes to muster media attention, lobby Congress, locate top-notch legal advice and organize successful protests and boycotts. Founder and president of the 25,000-member activist group Earth 2000, and recent recipient of the

Schweitzer Foundation’s Reverence For Life award, Seo is considered a powerful voice for his generation. At age 12, Seo formed Earth 2000 to save a 66-acre forest near his home from development. At 14, he organized protests against enforced animal dissections that resulted in a new statewide law. At 17, his massive letter-writing campaigns convinced several clothing chains to stop selling fur. “Our generation faces problems that didn’t exist when our parents were our age,” Seo says. He adds that “it’s not surprising that young adults feel hopeless about the future,” with so many environmental and social ailments plaguing their world. To counteract such hopelessness, X’ers are evolving from worriers to warriors.

Dorm Storming

A powerful voice for his generation, Danny Seo is the recipient of the Schweitzer Foundation’s Reverence for Life Award.

The Sierra Student Coalition (SSC) estimates that one out of every 100 calls coming in to officials on legislative issues are from college campuses. “For every moment you’re told you’re too young to do anything, that’s time that you could spend signing a petition or wiring a letter,” SSC founder Werbach told University of Texas students in Austin. The 30,000-member SSC is a national group of environmentally active college students who use “dorm storming” as a tactic for swaying votes and mindsets. “Dorm storming” means going from door to door at dormitories and residence halls, encouraging peers to lobby legislatures, do some letter writing and spread the word. “Stormers” were responsible for changing the mind of Senator John Kerry (D-Mass), who was to cast the deciding vote (ending a filibuster) on the California Desert Protection Act. This proved once again that-despite their reluctance to vote—the generation dismissed as apathetic slackers were changing the political process.

Kristin Mott, of the Do Something Foundation, a national nonprofit which encourages youth leadership, says, “We encourage all aspects of service, including environmental projects. Everyone we deal with here disputes the slacker mentality. So-called ‘slackers’ are giving more time, more energy and more money to volunteerism than any other generation. They’re doing a lot of work-just doing it differently.” (A recent study reveals that X’ers volunteer at twice the rate that Boomers did at their age.)

And across the country, AmeriCorps has recruited 25,000 members to volunteer -tutoring high-risk youth, building affordable housing, restoring state and national parks and cleaning up rivers and streams.

The Student Environmental Action Coalition (SEAC)-a network of over 1,000 college campuses nationwide, says its purpose is connecting students on particular issues, and lobbying at the grassroots level. While focusing on environmental issues, SEAC also recognizes that issues of racism, sexism, homophobia and other forms of oppression are intricately connected. Providing a wealth of resources and literature for students interested in “greening” their campuses, they also: complete campus environmental audits; encourage and educate on vegetarianism; propose alternative forms of transit on campus; support socially responsible business practices; encourage the purchase of eco-friendly products; and focus students on major campaigns like democratizing Burma and Headwaters clearcutting.

20/20 Vision’s Cheryl Haeseker says, “Elected officials need votes, and they know they have to reach this generation. Yet youth don’t seem to have any single hot button issue, so there’s no easy answer as to how to get them to the polls.” Indeed, the last election saw less than one-third of X’ers at the polls.

X’ers overwhelmingly believe that the political leadership ignores them, and they distrust the political process. The Who Cares study says that young adults “believe that younger leadership would represent them better,” and while caring deeply for their communities, “they express this concern by making a difference in their neighborhoods, not in the political arena.” Some 20 percent of 18- to 24-year-olds consider themselves “Independent” voters; and more X’ers surveyed said they’d registered to vote than actually did. Campus Green Vote, part of the Center for Environmental Citizenship, is countering such political apathy by training and educating students on environmental and political campaigns, while spurring students to register to vote. It also offers EarthNet, an up-to-date listserve where students can get current legislative information to make informed decisions.

Generations to Come

Youth for Environmental Sanity (YES!) is a seven-year-old project devoted to bringing international youth closer to nature. The one- and two-week camping trips take place at retreats, farms and environmental enclaves all over the U.S. “At a YES! Camp, you truly step out of your normal environment,” says cofounder Ryan Eliason, 26.

YES! was founded in 1990 by then-teens Eliason and Ocean Robbins, John Robbins’ son, in Santa Cruz, California. In addition to the camps, its performance troupe, the YES! Tour, goes on the road and has entertained more than 500,000 students with shows that mix music, skits and information about what young people can do for social and environmental justice.

A major YES! camp supporter is 85-year-old David Brower, whose role in leading The Sierra Club, then founding Friends of the Earth and Earth Island Institute are the stuff of legend. Brower says, “I love talking to young people. That’s how I recharge my batteries. I see hope that should be there and I feel the obligation of doing what I can do at my advanced age, doing some ‘downfield blocking’ to help make it possible for them to have the experience I had.” He says institutions are aware that previous generations-the ones in power now-are the ones that have caused the energy crisis, endangered species, and cleared the forest-“And I’d like to see young people say: ‘Hey wait you guys. You used it up. And we’ve got to use a different approach.”

“I believe in the righteousness of our struggle,” Brown says. “I just hope that whatever we do, that we make sure the next generation understands how we made the decisions we made. I think the way to do that is to ensure that the next generation is at the table, helping to make those decisions.”

WILLIAM BUCK has been a youth activist since 1985, and resides in California; TRACEY C. REMBERT is managing editor of E.