Terri Swearingen

The Long War With WTI

As a registered nurse and mother, Terri Swearingen, 40, knows a little something about persistence. For the last two decades, she has been making thousands of calls and speeches, conducting health surveys, appealing to Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) officials, pleading with the President, and making trouble for Waste Technologies Industries (WTI). Swearingen’s goal is nothing less than shutting down one of the largest toxic waste incinerators in the world, which was built in her hometown of East Liverpool, Ohio. She now lives just a few miles away in Chester, West Virginia with her husband and teenage daughter.

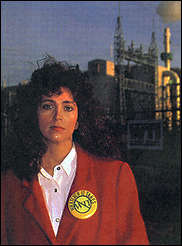

The shutdown of Waste Technologies Industries’ toxic incinerator—built 1,100 feet from an elementary school—has become Terri Swearingen’s never-ending mission.

1993 Robert Visser/Greenpeace

Swearingen’s tireless work made her a winner of this year’s prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize. She points out, again and again, that the WTI toxic waste incinerator is just 1,100 feet from an elementary school. The facility, now operational, is expected to burn more than 350 million pounds of hazardous wastes per year in two kilns, with the emissions reaching as far as Pittsburgh.

First proposed in 1979, the facility on the banks of the Ohio River was completed in a low-income neighborhood in 1992. The threat of the incinerator led Swearingen to co-found the Tri-State Environmental Council-a grassroots coalition of citizens from West Virginia, Ohio and Pennsylvania whose mission is to stop environmental racism.

In 1991, Swearingen led 1,000 residents in their first protest march; since then, she has been arrested over a dozen times for acts of civil disobedience against hazardous waste incinerators. In 1993, when WTI’s plant began limited operation, Swearingen quickly increased her activities to get the word out-gaining national attention by being arrested in front of the White House. (The following day, the Clinton administration announced major revisions in EPA policy concerning hazardous waste incinerators.) She was later instrumental in convincing Ohio’s governor to place a moratorium on new incinerators in the state, and the EPA to place an 18-month moratorium on newly-built incinerators. Swearingen blames a lax government and environmental racism for East Liverpool’s struggles.

E: You’ve been arrested over a dozen times. What did your civil disobedience accomplish?

Swearingen: In 1983, the East Liverpool incinerator became a national issue. That’s when I did the Greenpeace bus tour. We were in 25 cities in 18 states in a month. The Greenpeace bus was fueled by soy diesel, and this ecologically-sound bus tour culminated in Washington, D.C. We parked the big yellow vehicle-affectionately known as “Big Bird”-right in front of the White House and refused to move. We chained ourselves to the vehicle and to cement blocks, and it took six hours to jackhammer us out. The very next day, a New York Times article said that the EPA would overhaul its regulations, set new dioxin standards and create more stringent heavy metal standards.

When Clinton and Gore finally came to the incinerator site, they said it was a ludicrous place to put an incinerator. It’s 320 feet from the nearest house, and 1,100 feet from an elementary school of 400 kids. It’s also in a valley with air inversions eight out of every 20 days. Air inversions recently killed about 20 people in Pennsylvania by trapping air pollution over a community.

As far as the kids in the elementary school, and the kids in the community go-they are poor, and have families that are uneducated and just trying to keep food on the table.

But this isn’t just about children?

No. Eastern Liverpool has about 13,000 people. 500 of them are African-Americans, and all 500 live in the vicinity of the incinerator. It’s also an impoverished neighborhood that’s part of Appalachia. It’s a fairly rural area-far from the capital and elected officials.

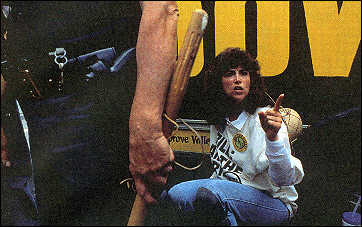

Arrested over a dozen times, Swearingen says civil disobedience is an effective grabber of media attention for environmental fights.

Photo 1993, Lauren Chelec/Greenpeace

When I first jumped into this, I was at ground zero. So I picked up Rush to Burn: America’s Energy Crisis. I read the book twice and highlighted sections with the people involved. Then I just started calling them up and asking for help. They said, “You’re going to have to deal with this yourself.” I have a family, and people forget that I’m not the head of some large environmental organization. I pay for the fight myself.

What’s going on in East Liverpool now?

Our community’s health is being affected. I’m also being sued for libel. WTI put a SLAPP [Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation] suit against me. I think that WTI is the epitome of everything that’s wrong with the regulatory system and our government. The WTI SLAPP suit is a camouflage to divert attention away from the issue—the incinerator. They attack your position and your First Amendment rights-and your children’s security. They can come into a community and say, “We’re going to build this because the EPA gave us permission to, and if you try and stop us, we’ll sue you.”

Everyone who’s seen this facility-even top public health experts-say it’s the worst place for an incinerator, parallel to designing transport for Death Valley around ice skates. Even the EPA’s regional director, Valdas Adamkus, who permitted this incinerator, admitted that WTI should never have built it where it is.

So the biggest problem is the location?

Have you ever heard of the Cerrell Study? It was conducted by Cerrell and Associates in 1986, outlining where companies could locate toxic or controversial facilities with the least opposition. It concluded that they should locate in poorer, uneducated or Catholic communities. Why Catholic? Because Catholics don’t usually question authority. East Liverpool is that kind of community. I think WTI tried to figure out exactly where the least opposition would be.

Since the incinerator started, have you been keeping tabs on health records in the area? Have there been significant increases in incidents of cancer or abnormal cancers, or anything else unusual?

In East Liverpool, the breast cancer rate per 100,000 between 1992 and 1995 was 41.5. The Ohio rate for the same period of time was 28.2. The U.S. average is 26.2. You can see how much higher East Liverpool is. Now there is also a cancer cluster in the east end near the site. There were two surgeries for male breast cancer in East Liverpool recently. And they went unreported. I spoke with the doctor who treated these men.

And there’s a lady who lives 800 feet behind the incinerator. She called me about a year ago. Her daughter, at that time, was 13. She said her daughter had already lost 50 pounds and was feeling weak and tired all of the time. She had a menstrual cycle that would last forever-

she was bleeding continuously. She had thrush in her throat and the anti-fungal medication doctors were giving her was not helping. She was seeing different doctors, and no one could tell her what was wrong. They even tested her for AIDS because they knew it was a problem with her immune system.

The mother called me, and her question was: Was this because of WTI? And I didn’t know how to answer her-because it could have been. It had been operating at that time for three years, and her daughter was in a sensitive period of development-puberty. And it was her immune system and her reproductive system she was having problems with.

On May 8, she told the EPA, “Three years ago, I had three healthy children,” and then proceeded to talk about all their health problems now. Her oldest daughter was checked for uterine cancer. Her condition is now degrading. She also relayed the story of her now-14-year old daughter in continuous pain.

Do you use the national Toxics Release Inventory database to help you gather information on incinerator pollution?

No, it doesn’t apply to incinerators. Remember your basic physics lesson-that matter can neither be created nor destroyed. WTI is saying it’s taking toxic waste from other facilities and destroying it. Whenever they do burn waste, it’s not really destroyed-it’s reduced to ash in a more concentrated form. All this dangerous dioxin is coming out of the stack. So the government says, “You have to reduce your dioxin emissions.” How do they do that? By putting pollution control devices on the machinery. But the dioxin has to go somewhere, so it ends up in the ash. So you’re not really reducing the pollution, you’re shifting it to another place.

People have to understand that. In a lot of cases, it has changed to something more toxic than what was put into the incinerator to be destroyed in the first place. Plus you have all this ash, where roughly 50 percent of what’s brought in has to be hauled off site and deposited in a toxic waste landfill. It’s got all of these heavy metals, including everything all those devices pulled out of the air.

Is that the primary danger?

The EPA itself said, “What we consider to be a serious risk at this time are accidents”-you know, fires and explosions at the site-because the homes and the school are so very close. There have been a couple of valve failures, and the school wasn’t even notified. And that’s pretty scary. What else is happening there that they are not telling people about? It becomes a matter of trust. It’s operating now. Can we trust these people to do their job properly, to tell us the truth, and be up front with the public so we can develop a level of trust? We do not have that.

What advice do you have for people who have a similar situation developing in their neighborhood? Where should they start?

I would organize several different groups. One, to get information about emissions-exactly what is coming out of that stack. Another group of people could be doing a community health survey. That’s what [Citizen’s Clearinghouse on Hazardous Wastes founder] Lois Gibbs did a few years ago at Love Canal. She just started going around to her neighbors and saying, “Look, talk to me about your health problems. What’s going on in your life? What about your kids?’ Keep a record of who you talk to, what date, and what they told you. Is there a pattern there? When did the problems first start? Was it the year the incinerator started up? Was it six months later? Then, compare it to what’s coming out of the stack. You know that, say for lead, you’re going to have problems with learning disabilities. So just look at what symptoms are related to lead exposure and what people are telling you.

Also, define your goal. Do you want the facility to be stopped, or just restricted? Start talking to people, and find out what others think. Go to them, and tell them what you’ve learned and see if they’re interested, so you can form an organized group. Then, put out a press advisory that you’ve started a organization to monitor the situation, and that will get the media’s interest. From there, it just involves a lot of research. But, make sure your information is accurate. That’s the bottom line. That is the way you establish your credibility.

Finally, remember your target. In this case, our target is not the state or federal EPA, although we call them on the carpet when there are problems. Our target is Von Roll-WTI’s parent company. That’s who we want to stop. You have to be very focused. Some people go off on tangents, and end up diluting their own effectiveness.

What was your initial goal when this started?

The incinerator’s complete shutdown. Again, I can’t say this enough: It’s the location, stupid. This thing should never have been built here. You don’t put an inherently dangerous facility that’s storing and burning the most hazardous toxic waste in the shadow of an elementary school, and right next to homes.

When WTI first came into this community back in 1980, nobody really knew what the ramifications of incineration were. It was a fairly new technology. There weren’t too many operating incinerators around the country at that time. We didn’t have anything to go by. People instinctively knew that this didn’t sound like a very good thing. And WTI used all the tricks in the book. They came in under the guise of a waste-to-energy facility, saying that they would provide cheap energy to the local community, and jobs to an economically depressed area. And that nothing would come out of the stack except water and carbon monoxide. But people questioned it.

Our fight is a tribute to grassroots organization. I’m proof that anybody can do it. People see that I’m ordinary, and realize that it doesn’t take a well-educated person to get things done for the environment. My message is “get involved,” because the government is not always going to protect your best interests. The government is getting out of control because no one is watching.

Von Roll is a multinational Swiss corporation that had its top executives convicted in a criminal trial for selling war materials to Iraq for Saddam Hussein’s Supergun. Eight years ago, I thought that if I took information to the appropriate officials, they would stop this. I was so wrong. But one of my greatest assets was my ignorance. Once you get involved, you’re going to learn the things they know along the way. You’re going to learn how to fight on their level. And hopefully, win.

TRACEY C. REMBERT is Managing Editor of E.