Thundering Wildlife

Zimbabwe Emerges as the Newest Eco-Destination

Coasting along fiery-red African waters, with the bellowing of hippos drawing attention from the pristine quietness of sunset, Zimbabwe’s Zambezi River offers an ideal way to get in touch with an unspoiled ecosystem. On one bank, five elephants stroll single-file to the water’s edge, where they snatch up lilac-plumed water hyacinths with their weathered trunks, then flop with a quiet thud onto the riverbank’s soft mud. And on the opposite shore, an adult giraffe casts a mottled reflection on the river’s glasslike countenance, gingerly leaning forward with front legs sprawled wide, to lap at cooling waters.

But Zimbabwe is more than just legendary wildlife. From Lake Kariba in the north, to the legendary Victoria Falls in the west, this pocket of teeming nature nestled above South Africa has the potential for a profitable ecotourism market. Once called Rhodesia and controlled by the British, a 1980 declaration of independence has returned a measure of racial equality to the country, whose English-speaking natives are concentrating the economy on agriculture, mining and wildlife-related tourism. And while airfare to Zimbabwe is the major expense (about $1,500 round-trip), the country itself offers very inexpensive lodging, food and souvenirs.

The explorer Livingston was drawn to the scenic beauty of Victoria Falls, considered one of the Natural Wonders of the World, almost 150 years ago. Today, this 354-foot-high attraction draws tourists for adventure sports as well as beauty: bungee jumping, skydiving, whitewater rafting and kayaking down Class 6 rapids, or soaring high above the falls on the “Flight of Angels” airplane tours are a few ways to appreciate the landscape. The misty spray from the falling waters can be seen from miles away-the locals call it “The Smoke that Thunders.” The falls are most impressive in April and May, when the Zambezi is at full flow.

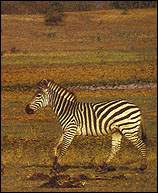

But Zimbabwe’s main attraction remains its wildlife. South of Victoria Falls, Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe’s largest, gives tourists a glimpse of almost every vivid creature found on the continent: there are zebras, baboons, elephants, lions, cheetahs, leopards, black rhinos, hyenas, giraffes, hippopotami, Cape buffalo (the most dangerous animal in Zimbabwe), wildebeest and impala, to name a few. Great baobab trees (called muuyu by local Shona tribes) provide shelter to 400 species of birds, while the changes in terrain—from open savannah to forest to dry scrub—give tourists a glimpse of each ecosystem at work. And while Zimbabwe is home to some 300 black rhinos, tourists are unlikely to get any pictures: They’re kept under constant armed guard for fear of poaching (populations totaled 3,000 in the mid-1980s). Decent and inexpensive lodging, from $3 campsites to $25 four-person lodges, is provided within the park, while The Hide Safari Camp outside Hwange offers two dozen guests private safari-style tents outside a much-frequented pan (wildlife watering hole) for excellent, but more expensive, wildlife viewing.

Another unrivaled spot is Bumi Hills Lodge, northwest of Hwange, on the southeastern side of Lake Kariba. From each room’s terrace, visitors can watch a majestic procession of elephants, impala, zebra and giraffe heading towards the lake, created back in the 1950s when the Zambezi was dammed for electricity. (Locals still fear the great Nyaminyami, a mystical serpent-headed god which seeks vengeance on the dammers of the river.)

Game drives (organized Land Rover tours accompanied by expert guides) are offered at almost every accommodation and national park, while walking tours are a little rarer—and much more dangerous—but give visitors a close-up look of smaller wildlife. Bumi Lodge wildlife guide Mike Rooney says, “To walk, you have to have fully-licensed guides or hunters with you because of the danger of charging animals.” Such walks could have you encountering wandering elephant bulls, as Zimbabwe is one of the few countries on the continent with a healthy pachyderm population. But it’s also home to the controversial conservation project CAMPFIRE, in which local people manage their own wildlife (with the scientific aid of park officials) and allow limited hunting of elephants, lions and other rare wildlife for money. The funds raised are reportedly used for conservation and development projects, but the toll has animal rights groups avidly protesting.

The best time to visit Zimbabwe is September and October, just before the rainy season, when water is scarce, and wildlife flock to the pan for sustenance. It might be a good idea to go now, before the country is overrun with eco-tourists.

TRACEY C. REMBERT is Managing Editor of E.