WIPP Lash

Doubts Linger About a Controversial Underground Nuclear Waste Storage Site

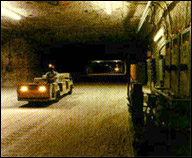

Twenty-five miles southeast of Carlsbad, New Mexico, and just north of the Texas border, lies a 10,000-acre plot of desert land owned by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). This is no ordinary piece of real estate: Far underground, nearly 2,150 feet below the scrub brush and cactus, is an enormous excavated network of salt bed tunnels slated to become the holding grounds for 850,000 55-gallon drums of radioactive nuclear weapons’ waste.

The $2 billion Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP), scheduled to accept the nation’s plutonium-contaminated trash as early as May 1998, has been mired in controversy for the past 20 years and faces one final hurdle: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) approval. Last May, the DOE signed a statement claiming that WIPP complies with all EPA regulations, and in August it submitted an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). If the EPA approves the application (and a draft compliance order was issued in October), then WIPP will open.

In the real world, however, things aren’t that simple. WIPP was conceived in the late 1960s, when a series of fires at the Rocky Flats nuclear weapons facility near Denver sent plutonium plumes into the city air. In response to the accidents, the DOE began shipping waste from Rocky Flats to a temporary site at the Idaho National Engineering Laboratory in southeastern Idaho. At the same time, it began hunting for a permanent and safe disposal site. In anticipation of the proposed opening, nuclear weapons facilities around the country accumulated-and stored in temporary holdings-enormous amounts of radioactive waste. Finally, in 1979, the DOE determined Carlsbad to be the ideal location for WIPP, and soon after, the site was authorized by the U.S. Congress. That’s when the protests began.

The barrels earmarked for WIPP contain nuclear weapons’ waste material contaminated by plutonium. While described by the DOE as medium- and low-level waste-including such seemingly harmless items as rags, rubber gloves and shoe covers-anything contaminated by plutonium can be extremely dangerous. Though most of the waste is considered safe enough to be handled without special equipment, radiation exposure, even in low doses, has been linked to cancer, genetic mutations, and immune system problems. The waste deemed unsafe for human contact is so radioactive that it must be handled by machines in special shielded rooms called hot cells.

It should come as no surprise, then, that the DOE would like to bury the waste a half-mile underground. But protesters don’t believe the issue will die so easily. Indeed, they don’t see WIPP as the solution to the nation’s nuclear waste problems. Deborah Reade, author of the book Everything You Always Wanted to Know About WIPP, points out that the proposed “solution” only hides nuclear waste from the public eye. “Radioactive waste has become a shell game where it is moved from place to place so that it is always out of sight,” she says.

Not only that, says Don Hancock, director of the Southwest Research and Information Center in Albuquerque, moving the waste could also prove to be a dangerous endeavor. “There is no scientific controversy around the fact that it is safer to leave all the waste where it is rather than bring it to WIPP,” says Hancock. “From a scientific and health standpoint, WIPP should not open.” But, acknowledges Hancock, these are not DOE’s priorities. “WIPP has always been politically driven, not scientifically driven,” he says.

Critics are concerned with the amount of radioactive waste WIPP will store, the lack of a leak-proof containment system, the unstable and brine-infested geology of the site, the potential for plutonium to leak into a nearby river, and the threat of airborne radioactivity. Reade claims that “the site is not safe, and can never be made safe.”

Of most immediate concern for scientists, however, is the inherent danger of radioactive waste transport, which environmentalists call “mobile Chernobyl.” Nuclear waste would be trucked from 10 weapons-production facilities across the country over the next 25 to 35 years. En route to New Mexico, the waste would pass through 22 states and several major population centers. The threat of an accident-not to mention airborne plutonium contaminating land, crops, animals, and people-leads many to fear an imminent nuclear disaster on our nation’s highways.

Whether the DOE will successfully sidestep its critics and go ahead with WIPP remains to be seen. More than $31 million has already been invested in promoting the site as the answer to the nation’s radioactive waste dilemma. But as the opening date of May 1998 nears and both sides prepare for a final battle-possibly in court-the WIPP site itself may provide the proof protesters need. Environmental critics say that several slabs of earthen roof-several weighing as much as 1,500 tons-have already caved in over the storage rooms, and that the walls and floors of the repository are bulging and cracking as geological forces do their work.

But Dennis Hurtt, a DOE team leader in the Carlsbad office, says the cave-ins were “preplanned in experimental areas, to test the rate of movement. There was nothing mysterious or dangerous about them, and to claim otherwise is being deliberately misleading.” Citing a review by the National Academy of Sciences, he describes the chances of a radiation leak as “extremely remote.”

If WIPP does open and that enormous piece of Southwest real estate becomes the nation’s latest nuclear waste holding grounds, critics-and a majority of the public-believe that at some point radioactivity will leak from the site. As Melody Stevens, a spokeswoman with the Albuquerque-based Citizens for Alternatives to Radioactive Dumping, puts it, “The question is not will it happen, but when. This is not a problem you can just stick underground and walk away from.”