Fracked To Pieces

In anticipation of hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” for natural gas coming to New York’s Catskill region, Jill Wiener made an unexpected career move. An artist who relocated from New York City to the Catskill town of Callicoon 15 years ago, Wiener is so upset about the proposed gas drilling that she’s running for office on a platform opposing it. She moved to the area, she explains, after discovering the perfect homestead there. “I live in the country on 60 acres with a beautiful spring-fed pond. I’m a potter. I grow chemical-free flowers. I depend on my clean water for everything. It [fracking] is not proven to be safe, and I’d never inflict this on the land I call home or on my neighbors or community. We have people running for office all over the shale. I’m running for town council because my councilman supports it. I didn’t want to do this—I wanted to sit in my barn and make pots.”

Drilling for domestic natural gas is one of the fastest growing sources of energy in the U.S. Based on all the industry media ads, natural gas looks like the un-fossil fossil fuel, the “safe, clean” source of energy for electricity, home heating and even for fueling a growing segment of the country’s transportation fleet.

Yet a growing chorus of critics—including some within state and federal government—is challenging the industry that’s always had a pass regarding many key federal environmental laws.

The biggest growth in production has come since 2004, as new technologies have allowed companies to drill wells horizontally into slick rock, a process that requires injection under high pressure of thousands of chemicals mixed with sand and hundreds of thousands to millions of gallons of water deep underground into hard rock shale formations to release the previously inaccessible natural gas within. Much of the criticism of the practice has focused on concerns about how fracking might contaminate drinking water wells. But a more fundamental problem may be that shale gas, which is predicted to grow from 15% of natural gas production in 2011 to almost half of production by 2030 according to the federal Energy Information Administration, is delaying and may even prevent the development of economically competitive clean, renewable energy.

Case in point: Texas energy tycoon T. Boone Pickens generated a big buzz in 2008 when he announced his plan to reduce U.S. dependency on foreign oil by greatly boosting both domestic wind energy and natural gas production, but in late 2010 he abandoned the wind component to focus exclusively on natural gas, citing its low price. He promoted it most enthusiastically for the transportation sector.

LOTS OF GAS, FEW SAFEGUARDS

Ninety percent of the country’s million-plus vertical and horizontal gas wells are fracked, i.e. , the rock holding the gas is fractured to enable more gas to flow out. But the added challenges of horizontal fracking—using higher pressure and more chemicals and more water—have made it the focus of environmental and public health concerns. The process is being used in deep shale formations in nine states. The federal Energy Policy Act of 2005 specifically exempted natural gas companies from complying with the Clean Water Act (it’s called the “Halliburton Loophole,” after the company formerly headed by then-Vice President Dick Cheney which invented the hydraulic fracturing process.) In fact, the oil and gas industry, while claiming it must adhere to federal regulations, is actually exempt from major provisions of many federal environmental laws, including the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, the National Environmental Policy Act and the Toxic Release Inventory.

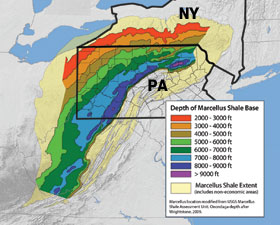

The Marcellus Shale extends through parts of New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Virginia and Ohio. Pennsylvania was an early fracking adopter, with 3,751 horizontal wells drilled in the state as of June 2011. There are fewer than 100 in West Virginia and just a handful in Ohio, according to the Marcellus Shale Coalition, an industry group. Media outlets including The New York Times, 60 Minutes and ProPublica have explored the pros and cons of shale gas development in that state, including reports of contaminated water wells in the western Pennsylvania town of Dimock. In December 2010, Cabot Oil & Gas signed a consent order with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection and agreed to install a water treatment system and create an escrow account for 19 homeowners in two townships whose water was contaminated, repair the cement casings the DEP said were the cause of the leaks, continue to test both the gas wells and water wells, and pay a $500,000 settlement to the DEP. Cabot complied with the consent decree but did not agree with the DEP’s assessment of the cause.

In addition, a New York Times article in August 2011 revealed a 20-year-old case of a water well in West Virginia contaminated by fracking activity. Reporter Ian Urbina wrote that no more cases could be identified because other homeowners who had reached settlements with gas companies had all signed non-disclosure agreements.

In New York, lawmakers passed a ban on shale gas development in 2010 that was vetoed by former Governor David Paterson, who then imposed a temporary moratorium. In any case, the governor can’t issue any permits until the statewide Supplemental Generic Environmental Impact Statement is complete, sometime in 2012. New York’s new governor, Andrew Cuomo, has proposed banning fracking in specific areas, while allowing it in most of the Marcellus Shale with safeguards in place. The proposal from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) would prohibit high-volume hydraulic fracturing in the New York City and Syracuse watersheds (the only state watersheds where water is unfiltered), including a buffer zone; within primary aquifers and within 500 feet of their boundaries; and on state-owned land including parks, forest areas and wildlife management areas. Drilling would be permitted on private lands under “rigorous and effective controls.” The July 1 statement concludes, “These recommendations, if adopted in final form, would protect the state’s environmentally sensitive areas while realizing the economic development and energy benefits of the state’s natural gas resources. Approximately 85% of the Marcellus Shale would be accessible to natural gas extraction under these recommendations.” A 60-day public comment period began at the end of August, although drilling opponents were trying to get it extended to 180 days.

COMMUNITIES DIVIDED

Local, regional and statewide groups have sprung up in New York to push for a permanent ban on shale drilling. Citing the injection of thousands of chemicals—some of which are carcinogens—and the pollution of up to a million gallons of fresh water each time a horizontal well is fracked, opponents say the process can’t possibly be kept clean or safe. The industry denies responsibility for drinking well contamination and points out that the EPA has acknowledged that so far it has not been able to link such contamination to fracking practices

Potter/political candidate Wiener is part of Catskill Citizens for Safe Energy, which formed in 2008 “in a reaction to landsmen coming around asking people to sign leases,” she explains. “There’s a very vocal minority of people that are for this; they’re supported by industry so their voices become louder.” An August 2011 Quinnipiac University statewide poll showed New York voters favor drilling the Marcellus Shale by up to a 47% margin for the jobs and taxes it would generate, even though a majority of them say they believe it will damage the environment. Meanwhile, the New York State-based Marist Poll queried residents the same month and found that 37% of New Yorkers oppose drilling, while 32% support it and 31% are unsure. Local polls in some Catskill region towns run as high as 80% against drilling.

In grassroots fashion, the 7,000-member Citizens for Safe Energy has no office, but its leaders “meet” online several times a day. “People are very frustrated on both sides of the issue,” Wiener says. “I sympathize with large landowners and dairy farmers who have been put upon by government-controlled milk prices and then somebody comes in and promises Christmas and you don’t have to do anything and you can continue farming. But people are getting sold a bill of goods. This is a gigantic environmental, public health and economic problem—it would completely change our economy. It is also a giant social problem. Communities are coming apart at the seams, neighbor against neighbor, and family members on either side of the issue. Thanksgiving dinners are not what they used to be.”

Wiener points to Louisiana as a cautionary tale. Although tourism, seafood harvesting and gas and oil extraction have co-existed there for years, drilling in the Gulf contributes to major erosion of the coastline and everyday spills along with spectacular disasters like the BP explosion in 2010. These substantially impact the other two major economic drivers, although industry promoters emphasize the resilience of ecosystems in their ability to recover from such assaults.

“The same thing will hold true here,” Wiener says. “Our biggest industries are tourism and agriculture. If we have drill rigs everywhere and possible contamination, I don’t know too many tourists that would come up here, battling thousands of diesel trucks.” She notes that Brooklyn’s Park Slope Food Coop came out in support of a moratorium and declared it wouldn’t buy any food produced where fracking occurs

Claire Sandberg is director of Frack Action, a statewide organization demanding a ban on shale drilling in New York. She’s not satisfied with the DEC’s recommendations. “Contamination is not constrained by arbitrary boundaries,” she says. “We don’t consider New York City and Syracuse protected—we don’t know how far methane and chemicals can travel. We’re not confident a 4,000-foot barrier around the watersheds will protect them.” She says upstate wells are not filtered and fracking would not be restricted there. And Sandberg adds that the proposed regulations don’t mention any restrictions on trucks carrying radioactive waste which is generated by radium in the wastewater. “There are also air impacts—a huge amount of diesel exhaust and cancer-causing chemicals being vented into the air.”

Echoing a series of articles in The New York Times, she’s doubtful that all the proposed wells will bring the riches they promise. “A lot of the profit comes not from pumping gas but from pumping up expectations among investors,” Sandberg says, adding, “A lot of landowners think they’re going to get rich on the royalties.

Opponents of drilling say the blowout preventers on the gas wells are no more reliable than the infamous blowout preventer on the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico that blew in April 2010.

After the comment period, the governor will decide how to proceed. “We hope Cuomo sees this [fracking] as a large political risk for him,” if he gives it the go-ahead, Sandberg says. “It could turn upstate New York into an industrial wasteland.”

RESISTANCE TO A BAN

Buffalo, which sits at the western edge of the Marcellus Shale, was the first municipality in New York to pass a ban on fracking in January 2011; a dozen smaller cities and towns have since followed suit. A DEC spokesperson says the legality of any local bans will be decided in the court

In at least some short-term good news for drilling opponents, the Delaware River Basin Commission (DRBC), which manages the watershed that supplies water to 15 million people in New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware, has put gas development on hold while it drafts rules to govern fracking. Draft regulations were published in December 2010, followed by a comment period that ended in April, during which 69,000 comments were submitted. The 83-page draft plan states that the commission has determined “that all natural gas development projects may have a substantial effect on the water resources of the basin.” The regulations, therefore, are “to facilitate optimum planning, development, conservation, utilization, management and control of the water resources of the basin to meet present and future needs.” Among other goals, they should “Link water quality and water quantity with the management of other resources,” “Recognize the importance of watershed and aquifer boundaries,” and “Avoid shifting pollution from one medium to another.”

Commission spokesperson Kate O’Hara says the DRBC, made up of the governors of the four states and a representative of the federal Army Corps of Engineers, is under no deadline to make a decision, adding that before drilling can begin, “Companies need to get permits from us and from their states. Drilling is going on already in Pennsylvania, but not the part that’s within the Basin.”

Andrew Revkin, former long-time environmental reporter at The New York Times and now full-time blogger for Times’ environmental blog Dot Earth, is impatient with the ban supporters. In a recent post he noted, “New York State Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo’s energy plans for the state are crystallizing. Through administrative moves, he has indicated that he sees the need to responsibly exploit the state’s enormous gas resource while moving toward ending nuclear power generation near New York City and its suburbs.” Revkin wrote that he opposes a ban “on the cash-strapped state extracting a fuel that—when produced responsibly—can be a vital part of the country’s, and world’s, transition toward a non-polluting energy future.” He referenced a BP scientist’s work showing how virtually all emissions from gas wells can be eliminated, and added, “It’s also worth remembering that while an important study indicated that drilling was associated with elevated concentrations of methane in some Pennsylvania regions, the same study found no evidence of water contamination involving chemicals used in fracking fluids. I’m all for finding practices that limit gas leaks, both underground and above. But I’m also all for noting the full scope of what science is revealing.

That study Revikin cited was conducted by Duke University professor Robert Jackson and his colleagues. In it, researchers analyzed the water from 68 private wells in Pennsylvania and New York and found methane levels 17 times higher in water wells near hydrofracking sites. But no contamination was found by fracking fluids. Methane, which occurs naturally in well water, isn’t regulated as a contaminant in public water systems under the EPA’s National Primary Drinking Water Regulations, but the methane identified in the study had a different “signature” and came from much further underground than naturally occurring methane, Jackson says. The peer-reviewed study appeared in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in May 2011 and points to methane from drilling operations migrating into the well water.

“The shale gas revolution has been a tremendous boon for this country,” Jackson says. “It’s domestic, it’s cleaner than coal…but it is extremely cheap right now and that low cost is providing a brake, I believe, on the implementation of renewables like solar and wind. It makes it harder for those renewables to penetrate the market. I think, done safely, hydrofracking can be helpful for the country; when companies get in a hurry, they make mistakes. The goal of our work is to help eliminate the mistakes.

Travis Windle, spokeperson for the Marcellus Shale Coalition, an industry group, insists that there are mistakes in Jackson’s paper. “There was no baseline established, so how can you say what’s an elevated level?” he asks, adding, “Pennsylvania has a long historic track record of naturally occurring methane entering private water wells; it’s not a new issue. We’re working with environmental regulators to mitigate this impact, the overwhelming amount of which is naturally occurring.” He adds that since this methane was present long before horizontal drilling was introduced, residents in many areas of the country “not only could but did light their water on fire,” which he says puts the lie to what was arguably the most compelling visual in Gasland, Josh Fox’s Emmy Award-winning documentary about hydrofracking. (see “Igniting Minds,”) However, Windle lauds the study’s conclusion that no hydraulic fracking fluids were found in any private water wells.

“In a perfect world we’d have pre-and post-drilling data for every house where we worked,” Jackson acknowledges. “Proving cause and effect is pretty hard but it’s [also] hard to look at those numbers and say there’s no relationship to gas well extraction.”

Jackson says his team is continuing to collect data. “We’ve been back several times this summer and expanded our geographic coverage and are re-sampling homes we sampled before that now have wells near them,” he says, adding that a lot of work must be done to determine the leak rates from different aspects of the drilling process. He’s called on industry to conduct a joint review of the process with his team, but has not been taken up on his offer.

A STUDY IN CONTROVERSY

An even more controversial study came out of Cornell University in April 2011, which posits that shale drilling for gas creates more greenhouse gases over the first 20 years of methane emissions to the atmosphere than coal production over an equivalent time period, and that over a 100-year timeline, the footprint is comparable. While this conclusion may shock most Americans—since for years scientists asserted that burning coal creates the largest greenhouse gas footprint of all fossil fuels—study co-author Robert Howarth points out that his research was the first in the peer-reviewed literature on the greenhouse gas footprint of shale gas.

That conclusion certainly contradicts the gas industry’s own intensive public relations campaign proclaiming natural gas the clean fuel of the future. Howarth, like Jackson, acknowledges he didn’t have the best possible data on methane leakage. “In our paper itself, we say data are limited and their quality is less than desired. Why is that? Does the industry have better data? They say they do. Have they shared it with anyone, even the EPA, which requires it by law? No. We were pretty cautious and careful and ran it by lots of experts, some of whom we thought would be critical,” he says. “We knew it would face a lot of scrutiny.” It went through two reviews before being the first paper on the subject to be published in the peer-reviewed journal Climate Change Letters. Industry spokesperson Windle says the report has been “debunked,” citing poor data and pointing to different carbon footprint numbers from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), normally considered the gold standard by environmentalists.

The key to Howarth’s claim is new research showing that methane is 105 times more potent as a greenhouse gas, pound for pound, than carbon dioxide in the first 20 years after its emission, and 33 times more potent over 100 years. The 1996 IPCC report indicated it was 21 times more potent over the first 100 years, which is the estimate the EPA still uses. The IPCC 2007 report changed this to look at both 20 years, where methane was found to have a global warming potential of 72, and 100 years, where methane was found to have a global warming potential of 25 (the global warming potential dissipates over time). “The IPCC authors said they would have used the newer [2009] data if they’d had it,” says Howarth. “The way the scientists in the IPCC update their report is by using the very best and most recent science.”

He and his colleagues estimated that 3.6%-7.9% of the lifetime production of a well is purposefully vented or leaked into the air during the lifetime of a hydraulic shale gas well—up to twice what escapes from conventional gas wells.

Howarth adds, “In the academic world, this didn’t catch people by surprise, because other studies on natural gas have been published in the past 15 or 20 years; it’s just that policymakers have not been paying attention. The conclusion is that natural gas in general and shale gas in particular is not the clean fuel people think and until more research comes along and we have the best data out there, it ought to be a call for governments to go very slowly, not to view this as a panacea for the next several decades of fuel. And it ought to be a call for governments to fund better research by objective third parties so full information is available for making long-term decisions.”

Windle says interest is high among investors in developing shale gas in New York. “It’s a very big deal, especially since those areas are close to major markets. We think New York is well-positioned to develop these clean-burning, American resources and deliver them to a significant population base in the United States.” He says states are doing a good job of “tightly regulating” the process, so there’s no need for oversight by the EPA, which the industry has opposed, and he dismisses any environmental or public health concerns. “[EPA Administrator] Lisa Jackson recently told Congress that hydraulic fracturing has never impacted groundwater,” he says. “She’s absolutely right. Despite that, we’re continuing to work as an industry to help make this process even safer than it [currently] is.” Critics counter that many states have weaker regulations than the federal government, and that in practice—since massive budget cuts in many states have reduced the environmental agencies’ workforces—regulation has weakened even more.

The EPA is studying fracking’s impact on drinking water, including from the radium-laced wastewater that is pumped out after a well is fracked, and is expected to release preliminary results in 2012, followed by a full report in 2014. Many fracking opponents criticized the agency for making its study focus so narrow.

Meanwhile, President Obama’s energy secretary, Steven Chu, appointed a high-level commission to investigate the safety of shale gas development in May 2011. In a preliminary report in August, the seven-member panel—six of whom have financial ties to the oil and gas industry, and one of whom represents an environmental group (Environmental Defense Fund)—came down firmly on the side of drilling, recommending neither a moratorium nor a ban, but saying more regulations may be necessary to protect public health and the environment, and proposing more transparency in making information available to the public. Among its recommendations are keeping a lifecycle record of water used in the process, from withdrawal to disposal, and improving air quality monitoring around drilling sites with efforts to reduce methane emissions. It also called on the government for more research and development funding.

“America’s vast natural gas resources can generate many new jobs and provide significant environmental benefits, but we need to ensure we harness these resources safely,” Chu said in a release.

Opponents say they will keep fighting, town by town, state by state and nationally for a ban on a practice whose safety, they say, cannot be ensured.

MELINDA TUHUS is an independent print and radio journalist who has worked with In These Times, The New York Times, Free Speech Radio News and public radio stations.