Proceeding With Caution

In the Wake of September 11, Environmental Direct-Action Groups Change Their Tactics

On the morning of September 11, Congressman Don Young (R-AK) warned against a rush to judgment about the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Young told a reporter for the Anchorage Daily News that responsibility could lie with groups other than Islamic fundamentalists. "If you watched what happened in Genoa, in Italy, and even in Seattle, there’s some expertise in that field," said Young. "I"m not sure they’re that dedicated, but eco-terrorists

there’s a strong possibility that could be one of the groups."

Young soon joined his colleagues in condemning Osama bin Laden, but the targets of his original accusations are not entirely at ease. Though absolved of responsibility for the terrorist attacks, environmental and anti-globalization activists—particularly those who engage in direct actions—are facing a changed world in which they must ponder the future of their tactics.

"I think almost everything will need to change in the way we do direct actions," says Mike Brune, campaigns director for Rainforest Action Network (RAN). RAN counts civil disobedience among the tools it uses to challenge corporations with poor environmental records. While underscoring the need for future actions, Brune says direct-action groups need to weigh the political realities of protest in a terror-shocked world. "There’s a definite concern that doing high-profile or confrontational direct actions now isn’t the best strategy."

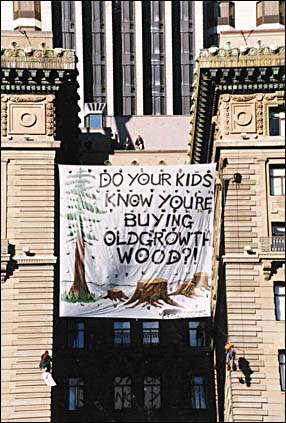

Direct-action groups trace their philosophies of nonviolence to the civil rights movement, Mahatma Gandhi’s teachings and even to the Boston Tea Party, although their style of protest is distinctly modern. Creative confrontation for environmental causes blossomed in the 1970s and "80s, when groups such as Greenpeace conducted dramatic actions like smokestack parachute jumps, high-speed motorboat protests and daring banner-hangs from landmarks such as the Statue of Liberty. More recently, RAN has engaged in actions involving banner-hangs and giant inflatable props, while the Ruckus Society has helped organize the street protests now synonymous with the anti-globalization movement.

Though styles differ, these groups share a core principle: In order to bear witness to an injustice and uphold a higher moral law, a lesser or unjust law may be broken. The effect can be powerful. "Direct action allows us to symbolically challenge business as usual and to crystallize an issue into its essential conflict," says Brune. To succeed with the public, this approach requires an audience willing to forgive minor transgressions in support of noble aims. In the wake of September 11, demonstrators now worry that their actions will be viewed as unpatriotic or inappropriate and that their concerns will be dismissed. To protest successfully, organizers say, the mood of a nervous public must be carefully gauged.

"Folks who practice direct action are going to have to be savvier than they’ve ever been," says John Sellers, executive director of the Ruckus Society. "They have to see what the American public is dealing with and what our shared experiences are." At action camps around the country, Ruckus has trained hundreds of activists in climbing and blockading skills, as well as ways to peacefully engage law enforcement and security personnel. Sellers sees a fine line that activists must now walk when engaging in civil disobedience. "It’s going to be particularly important that we do very inspiring, extraordinarily well-messaged, and obviously nonviolent actions."

Anti-globalization protests, in particular, have been marred by violent conflicts between police and demonstrators. Clashes at the G8 summit in Genoa last July led to the death of an Italian protestor, and these battles have provided scapegoat-fodder for politicians like Young. The terrorist attacks make it especially important, says Sellers, that protestors refine their message and practice proactive nonviolence. "The task of the globalization movement is to turn inward now. We’ve got to transform ourselves from a protest-based to a solution-based movement," he says. "We can’t get bogged down between cops and protestors."

As political obstacles abound, increased security measures since September 11 are also making the practicalities of protest difficult. In early November, the California National Guard was dispatched to protect the state’s major bridges from possible terrorist attacks. Sellers, who helped hang a banner on the Golden Gate Bridge with RAN in 1996, says the additional security will make high-profile actions a challenge but not impossible.

It’s an opinion shared by other organizers. "Initially, we thought, "Is this going to continue?" But we’ve been in these situations before," says Willem Beekman, action team coordinator for Greenpeace USA. As a 30-year-old international group, Greenpeace has dealt with intense security before, conducting actions in places such as Lebanon, China’s Tiananmen Square and the former Soviet nuclear test site at Novaya Zemlya. Like RAN and Ruckus, Greenpeace temporarily suspended direct actions after September 11. But after a short break, it resumed activities in countries such as Germany and Brazil. Beekman says that when the time is right, Greenpeace will resume its peaceful protests in the U.S., and that it will adapt to the tightened security. "We just have to be creative and find a new niche, as we’ve done for the last 30 years," he says.

One form of direct action—radical animal rights protest—has notably not slackened. The Animal Liberation Front has claimed credit for such post-September 11 actions as a firebombing at a federal wild horse corral in northern California, a fire at a primate research center in New Mexico and several animal releases in Idaho. Some actions attributed to the Earth Liberation Front have also occurred.

While concerns about message and security will likely subside in time, the effects of attack-related legislation may be a nuisance for years to come. Of special concern is the USA PATRIOT Act—the sweeping anti-terrorism package signed into law on October 26. Many in the activist community see the bill as excessively broad and a threat to their civil rights. "While we support laws to fight terrorism, this was hastily written," says Beekman. The law’s broad definition of terrorism could be construed to include peaceful protestors, say organizers. "We can see how opportunists may take advantage of security fears to stifle political dissent," says Brune.

Questions remain regarding the approach and tenor of direct actions in a terror-stunned country, but one certainty organizers agree upon is that the protests will eventually continue. "We certainly need to think twice before scaling the tallest building in a city or hanging a banner off a bridge," says Brune. "But if old-growth forests are still falling, we"ll be sure the American people hear about it."